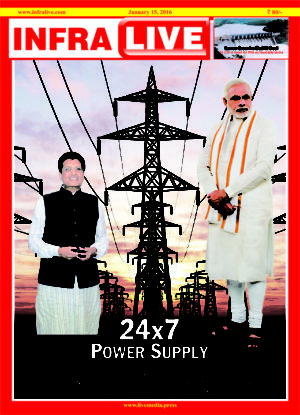

Political parties like the AAP have made freebie culture in the power sector their electoral gain strategy. This so-called ‘Kejriwal model of governance’ is bad economics, distorts our democratic process and a certain roadmap for future debt traps which carry high risk of becoming unmanageable and even toxic.

After a failed 49-day coalition with the Congress in 2014 in Delhi, Arvind Kejriwal rode to power in 2015 with the promise of free power. Free power has been extended, enlarged and newer categories added, the genie is out of the bottle and has been injected into the electoral process. Long considered the bane of policy reform, the cover story details the expanding footprint of free power under AAP and its overwhelming impact on the health of the discoms.

This strategy began in Delhi in Feb 2015 with a 50 per cent subsidy for domestic category consumers who used electricity upto 400 units in a month. Initially, this had a time-bound applicability but was extended for Kejriwal’s whole first term. Just months ahead of Elections 2020, announcements were made for full waiver of electricity bills for consumers with 200 units ie “ZERO BILL”, and from 201-400 units, the waiver was restricted to Rs 800 every month. In the 2020 Elections held in February 2020, he returned as the chief minister for the third time winning 62 seats out of 70 seats. On April 20, 2020, the announcement of the subsidy extension to 1984 victims of Sikh riots. He granted full subsidy ie “ZERO Bill” for families restricting the usage under 400 units in a month. The messaging of this action for Punjab elections due in March 2022 is not lost on anyone.

State elections are due in March 2022 in Goa, Manipur, and Uttarakhand, while for Uttar Pradesh it is due in May 2022. AAP is campaigning in all states on free power as its ‘governance model.

But is this really tenable?

YoY, this has meant the Delhi government shelling out more as subsidy support from the budget for the discoms. It has led to a bad cross subsidy structure, with industrial and non-domestic consumers forking out more amounts each year. The centre’s directions that the tariffs should not fluctuate more than 20 per cent from one category of customers to the other is also not being followed in Delhi. And then there is the huge outgo on interest payments that discoms endure as they struggle with cashflows even as there is accumulation of regulatory assets on balance sheets. Also in this edition, our special coverage on fuel prices and how the centre is resolving it.